I remember visiting my uncle at a NASA design lab sometime in the mid-80’s – it was a huge cavernous room that he explained used to house the computer. A computer his graphing calculator could draw circles around. It was a powerful visual reminder how quickly computing technology advances – components are smaller, more powerful, and simpler to use.

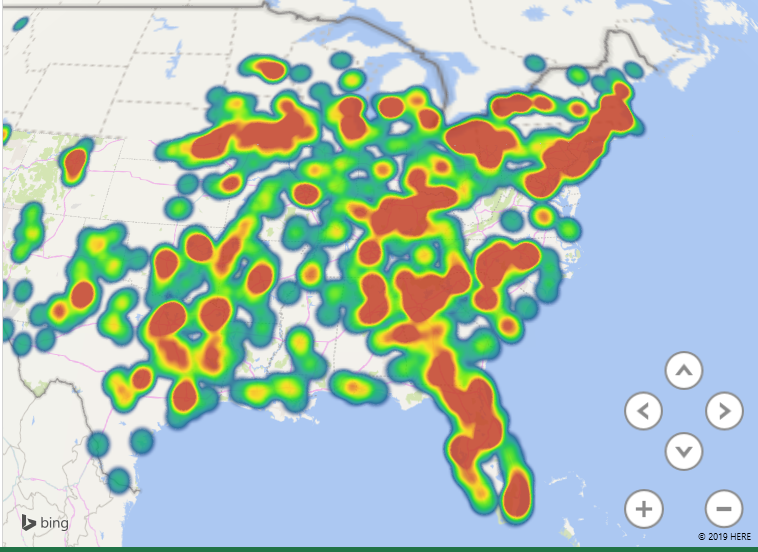

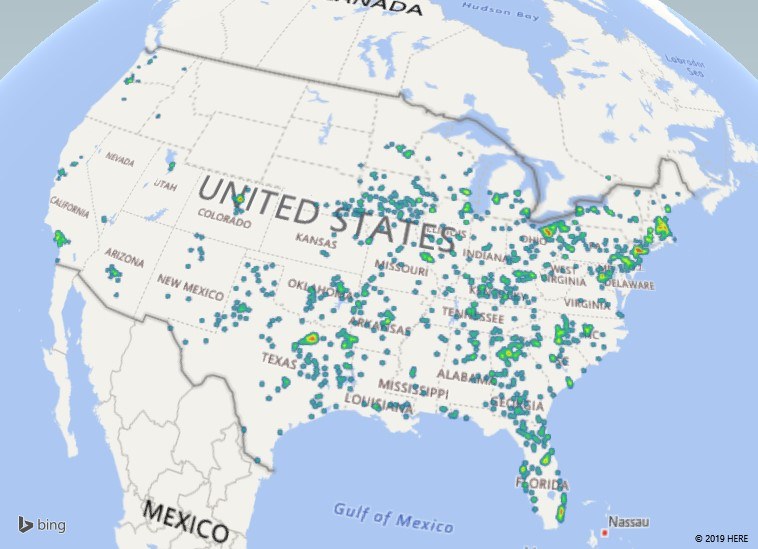

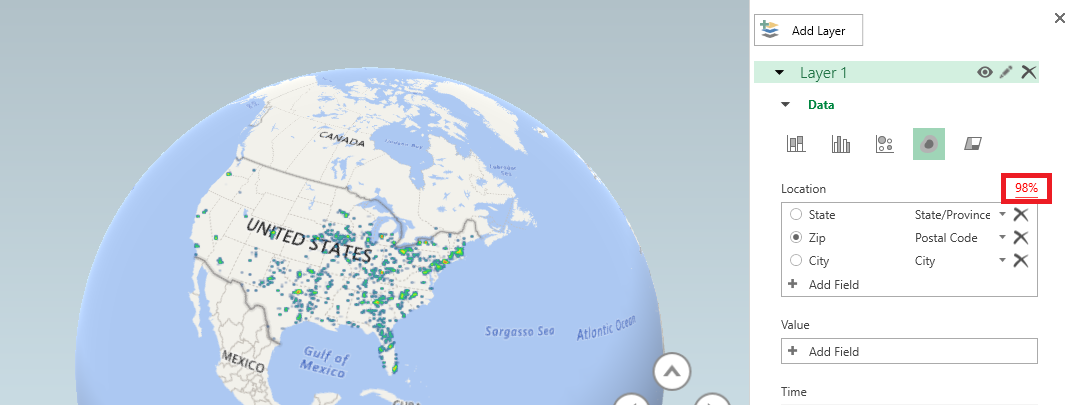

More than two decades ago, I wrote a visualization application that presented a graphical representation of the geographic distribution of records. Which is a long way of saying it showed where something happened to a lot of people. The application was part of a cooperative effort between the FBI and local law enforcement – a data mining project meant to identify serial offenders across jurisdictional boundaries I wanted to be able to visualize where different types of crime were occurring and identify anomalies, so I built a program to do so. It took months to develop and took hours to crunch values and draw a map. The first time I used Excel to visualize frequency distribution on a map, I thought of that NASA computer room. What used to take a high-end Unix server with a RISC processor and tonnes (for the time) of memory – not to mention an entire summer of code development – is clickity-click and done on my little laptop. And the results are nicer:

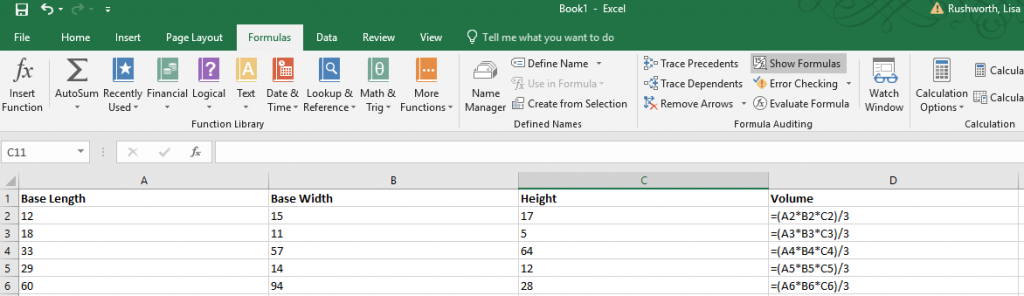

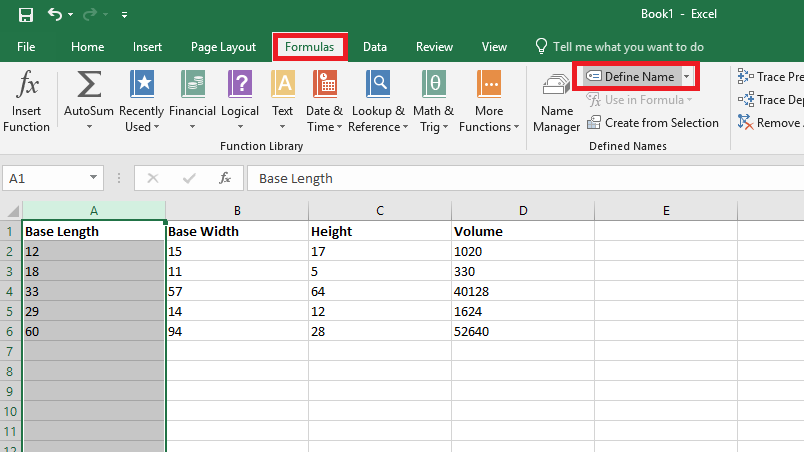

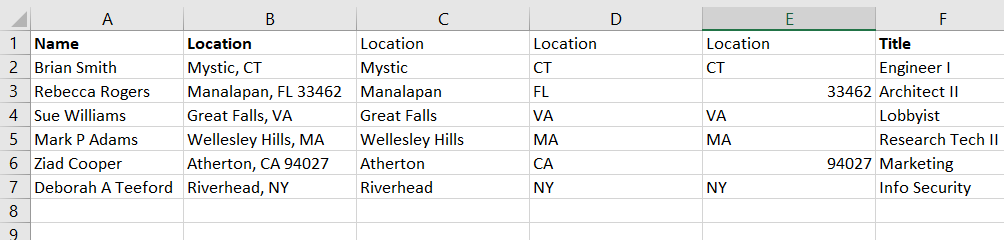

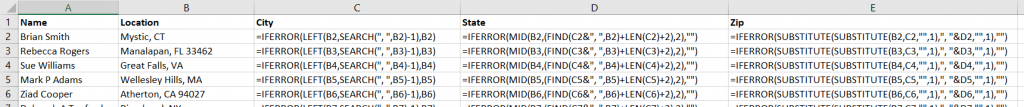

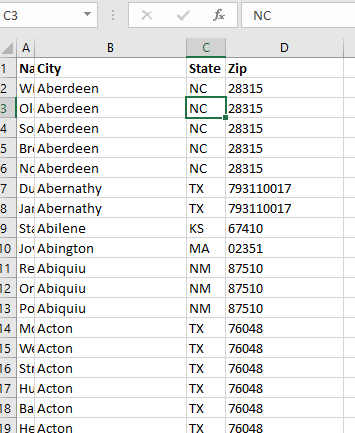

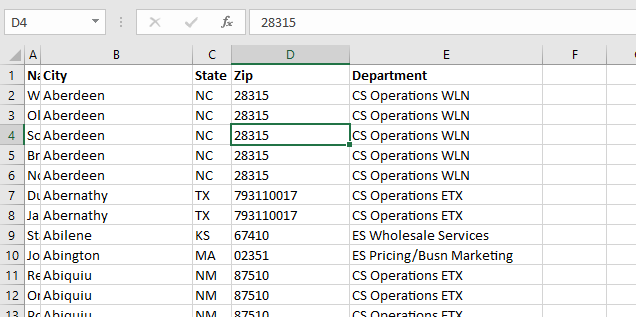

How do you create this type of visualization? First you need data with something that is mappable – the example here is going to show the office locations listed in PeopleSoft. Click within the data set.

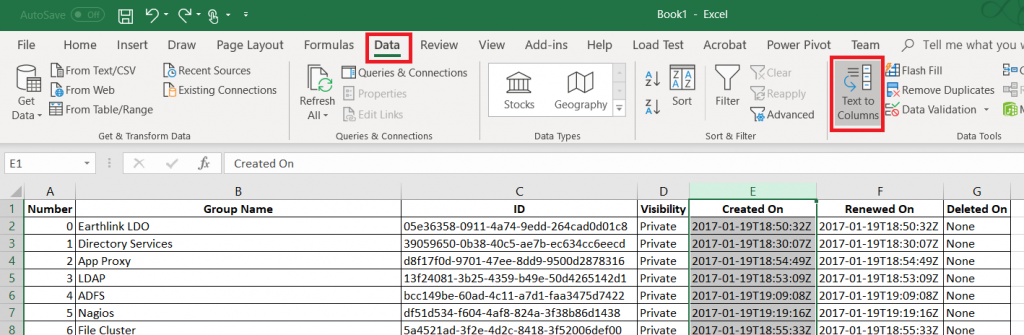

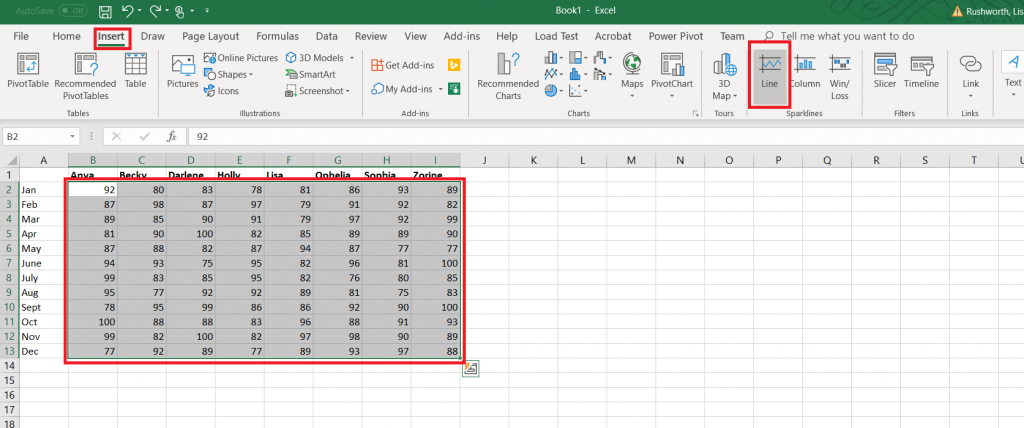

On the ribbon bar, select “Insert” then select “3D Map” in the “Tours” section.

If you have not used it before, you will be asked to enable data analysis service.

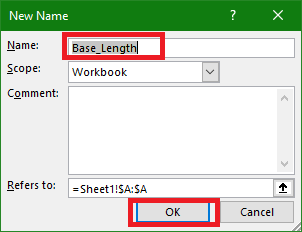

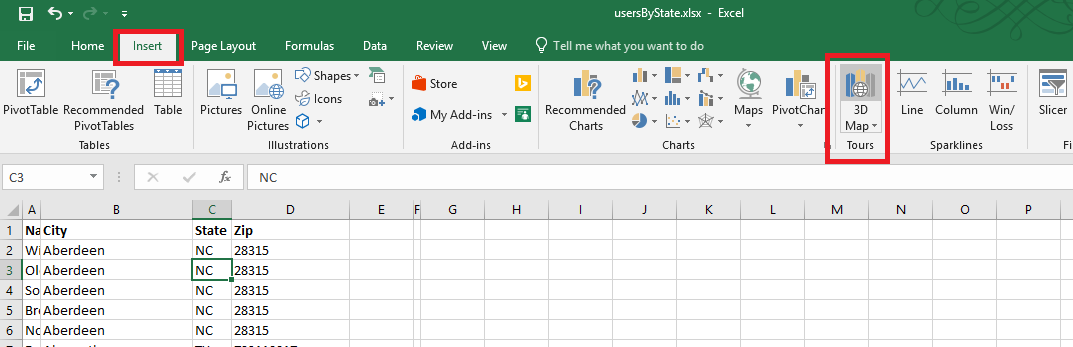

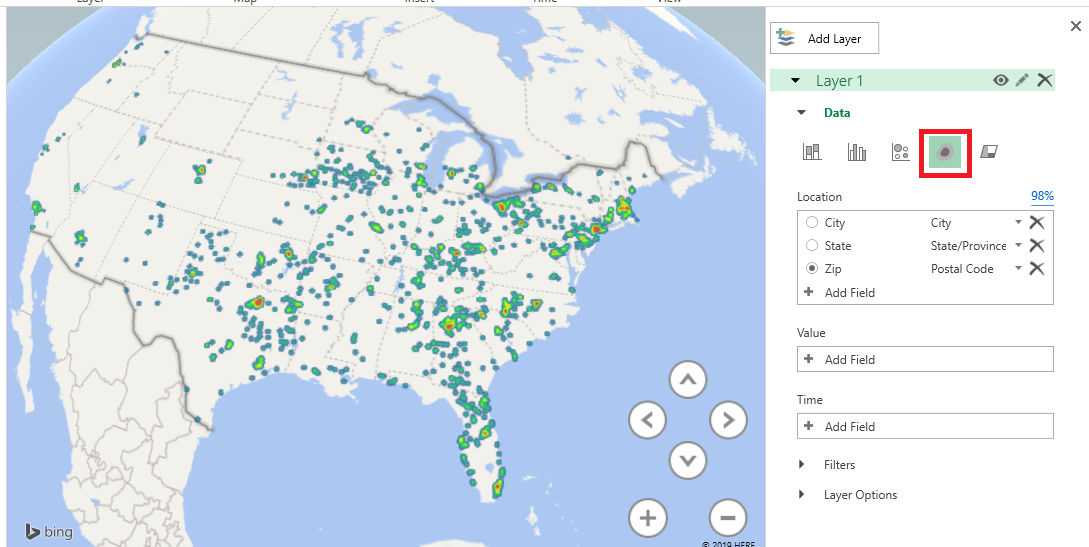

A new window will be displayed – select the column you want to map. Here, I am using zip codes, which is mapped to the “Postal Code” field in my spreadsheet. If your fields do not map automatically, you will need to click the drop-down next to a location data type and select the appropriate column.

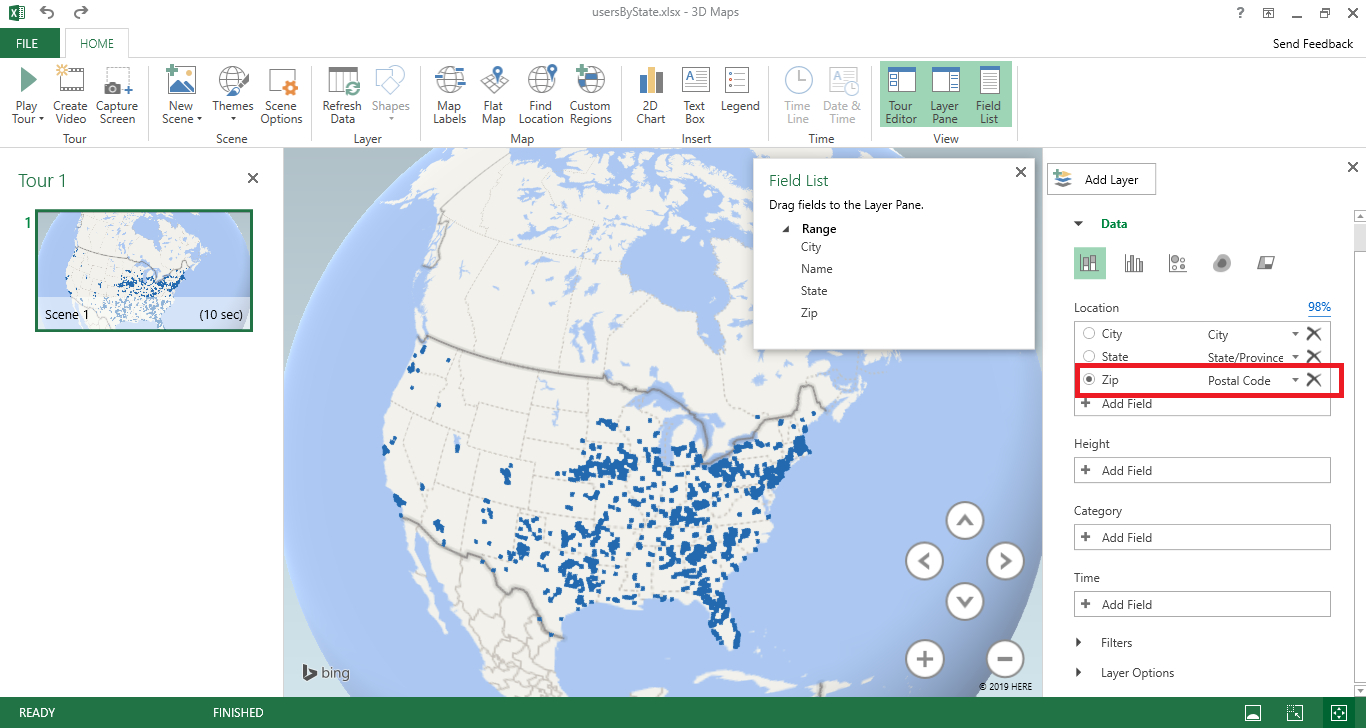

There are different types of visualization – here, I have switched to a “heat map” where the color of the blob represents how many records fall into this zip code. It is a quick way of identifying clusters – hot spots.

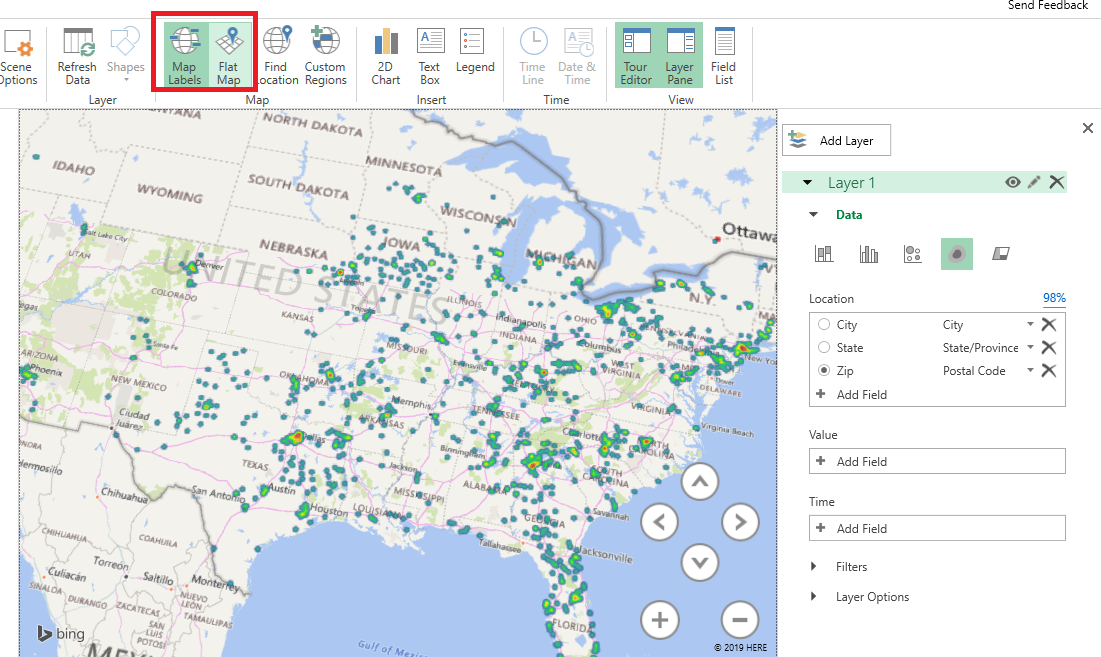

You can control the look of the map as well – here, I have switched to a flat map and added location labels.

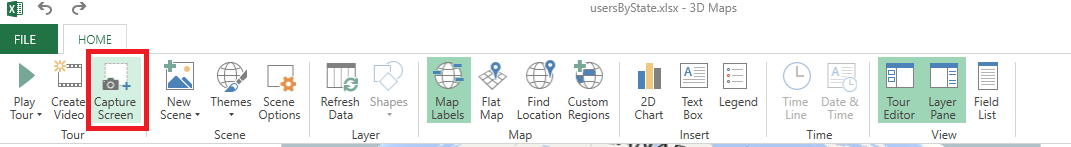

If you would like to include a copy of your map in another program – say, this Word document – select “Capture Screen” from the ribbon bar. You can also create a video to show an animated view of your map (zooming in on specific locations, rotating the globe to see people over in Mongolia)

After you’ve clicked “Screen Capture”, just paste and an image of your map will be inserted into your file – see!

Going A Little Farther:

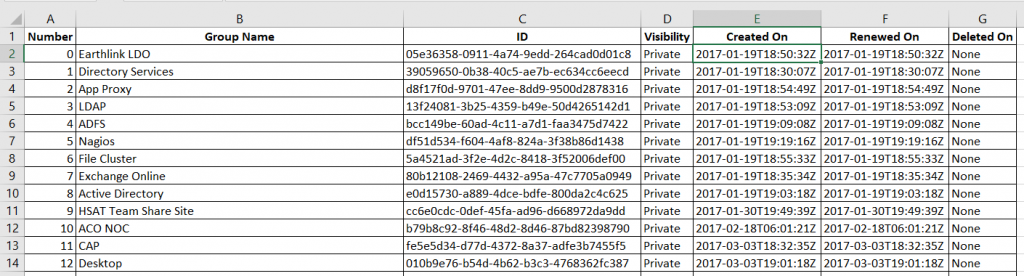

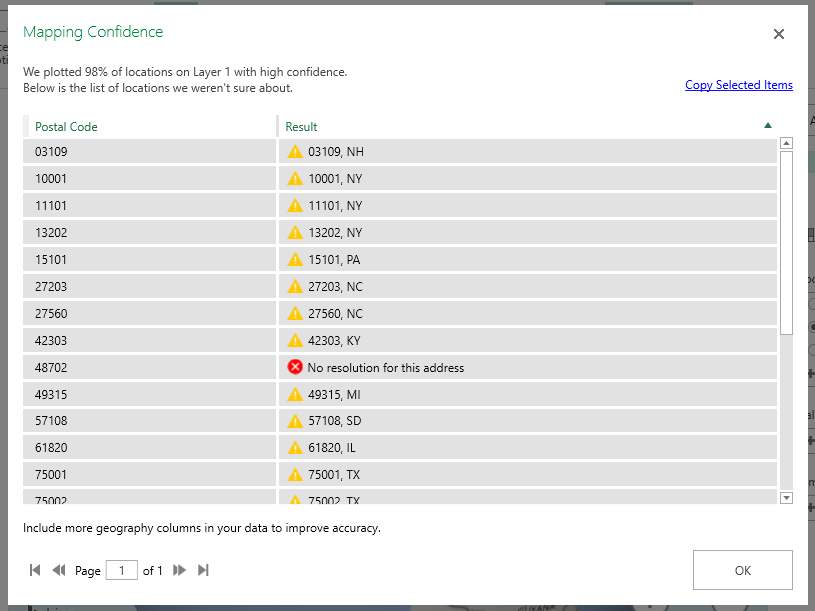

Data isn’t perfect, and even when the data looks good it may not map properly. My sister used to live on a street in New Jersey that does not exist on a map. The post office affirmed it was the correct address, but UPS and FedEx claimed it didn’t exist. It was funny to me, but I wasn’t the one trekking two kids down to the neighbor on the main road who nicely accepted packages for her. She moved before they ever got the address situation sorted, but I’ve got first-hand experience with addresses that don’t map in some systems but are perfectly fine in others. Why do I mention this? The map visualization provides a “Mapping confidence” statistic – it is the percentage that appears above the box where you select the location data to be mapped. 98% is pretty good – there are a handful of records that don’t appear on the map … but the data I am presenting is a decent representation of our employee office locations. A low percentage would indicate that your map does not accurately convey your data.

What if my map confidence level is low? Click on the map confidence value to see what didn’t map. There are some marked with a result that is questionable – spot-checking them, 03109 is Manchester NH and 10001 is New York, NY. The one with no resolution, according to the US Postal Service lookup isn’t a valid postal code. If your data is wrong, fix it 😊 In cases where the data is right but the application isn’t confident about the location, you can add additional data to make the address more specific (here, I might increase the confidence by having the zip+4, or including the street address in my data set).

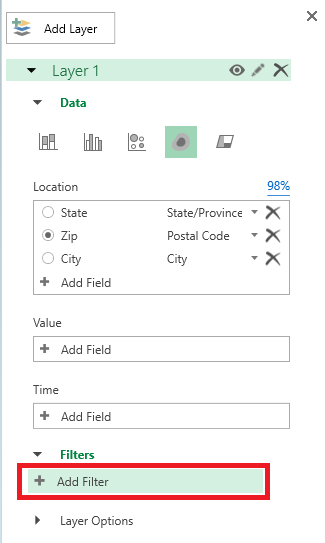

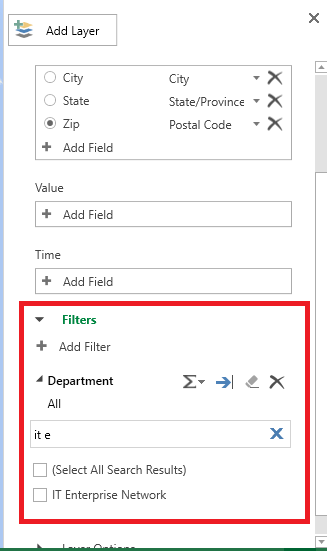

You can filter data in your map – first we’ll need some field on which to filter. Here, I’ve added the employee’s department to my data set.

On the right-hand pane, expand “Filters”. Click “Add filter”.

Select the column on which to filter data. A unique list of values will be presented – you can scroll through it or start typing the value to search. Once you find what you want to display, click the check-box before the value.

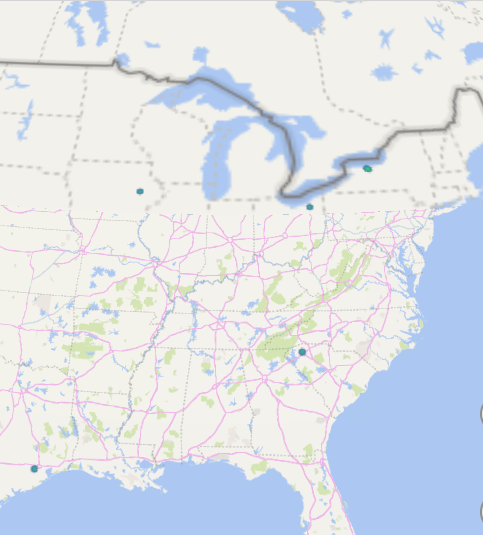

Now we are visualizing where people in my department work.

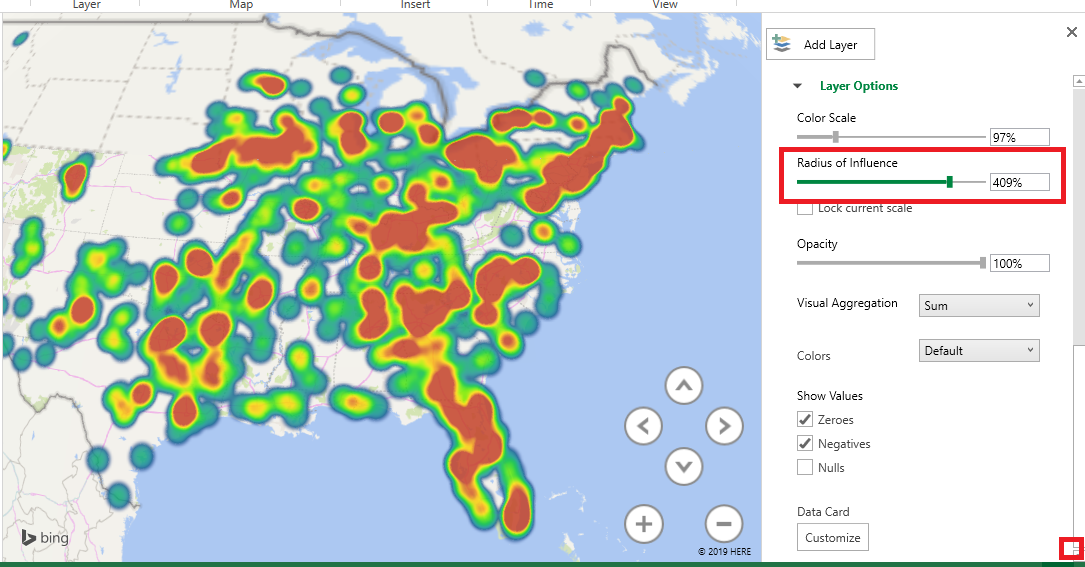

If your data is hard to see – records are distributed out fairly evenly across the map – you can increase the area of influence to make smaller clusters easier to identify. Scroll to the bottom of the right-hand pane and drag the “Radius of influence” slider to the right. If you have very clustered data, you can drag the slider to the left to turn a large red blob into a more nuanced visualization.

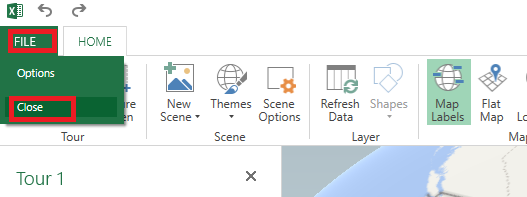

When you have finished visualizing your data, click “File” on the ribbon bar and select “Close”.