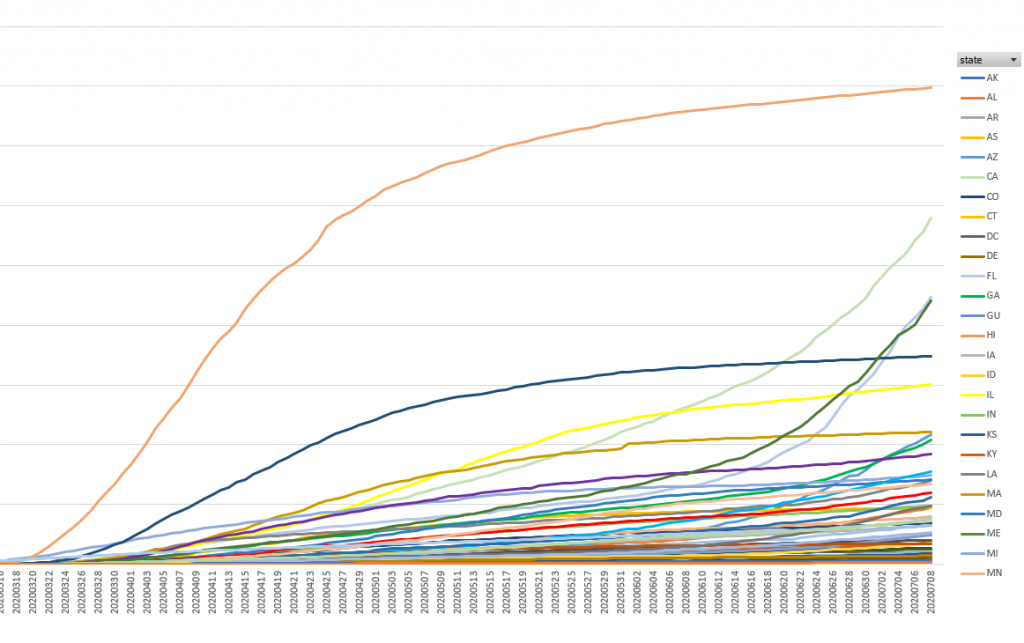

I question the logic behind the “the worst is past, and it wasn’t as bad as we thought” faction that’s drove the Memorial Day partying and is gearing up for the 4th of July celebrations. The decrease we see in the NYC metro is impacting nationally aggregated data. NY and NJ have significantly reduced infection rates (and have since late April/early May). MA as well. Most other states have seen increases. Since the NYC metro had an oversized representation of cases (some 6% of the national population had, in late March, some half of the national infections), the reduction in cases there has had an oversized impact on nationwide data. Break the infection rates out by state, though? There are a lot of lines heading up, and steeply.

Hospitalization rates are already heading up outside of the NE corridor. Again, the drop-off in the “New England” and “Mid-Atlantic” buckets hide increases in aggregate. Death rates don’t have such a clear upward trend. Yet. Infection is a leading indicator, followed by hospitalization rates (it’s not like you are in the hospital on day one. Most people I’ve seen interviewed say they felt sick for a week or two), *then* death rates a month or two after hospitalization. We’ve seen infection rates on the increase since June. We’re starting to see hospitalization rates increase. I don’t doubt we’ll see death rates increasing toward the end of July. I don’t know if this misrepresentation of aggregate over partitioned data is a deliberate attempt to obfuscate the current risk level or a more easily comprehended visualization (my chart with 50 lines is a lot more difficult to read that the single-line national infection count graph). But the impact on public perception and public policy is dangerous.

What bothers me, though, is that … even if someone believes the mortality rate dropping significantly as more young/healthy people get infected or we “get better at treating it” or whatever their mental excuse for partying and venturing out without any type of protection, the hospitalization numbers *are* going up. It’s certainly better to go into the hospital for a month or two and emerge alive than to die alone in the COVID ward. Personally? I want to avoid a month or two on a ventilator. It’s a rather unpleasant experience. Not to mention the personal and national economic impact from millions of people out of work – the lucky ones have insurance that covers something like 80% of their normal salary, the less ones need SSDI, and the really unlucky ones have nothing. Even if hospitalization was a fun holiday experience? At some point, health care resources are maxed out; then resource constraint impacts mortality rate.

Risk mitigation isn’t about taking extraordinary action to avoid black swan events. When I worked in Arkansas, there would be an ice storm that shut down travel for a few days. The first year I moved there, it was a serious storm that shut down most of the state for a week or two. Access to the company network was via dial-up. We had some number of PRI’s — maybe ten, which would be 230 dial-in lines. Normal operation, we had fifty or so lines free. Ice storm? They were maxed out constantly. After that first week-long ice storm, the company executives demanded IT figure something out because they were unable to get on network. The company had 20k employees, which would require 800+ PRIs (a reasonable analysis was about 10k employees who could work remotely, so ‘only’ 400 PRIs) and the dial-in gear so those lines went somewhere. For the low, low price of a few million, we could ensure everyone could dial into the company network simultaneously. Of course, no one wanted to fund that initiative. What we did implement was a dedicated executive dial-in access number. One PRI, with one small modem bank, provided access for the 20 people who were special enough to get the number (yes, there was an authorization group preventing access by the unwashed masses who had the number). And the three IT people who supported those executives. It cost more than nothing, sure. But it was a reasonable expense to address the most critical part of the issue. In the subsequent ice storms? Lower-level employees would complain about busy signals on the VPN, their complaint would work its way up the chain, and the executives would pull out my multi-million dollar proposal to fix a problem that averaged two days a year. Technology advanced, and IP-based VPN became a thing. It has functionality beyond Arkansas ice days, and the company invested in it. Now everyone can connect to the network during the ice storm. A fairly reasonable cost that has utility 24/7.

For some reason, people are treating masks like the multi-million dollar VPN project. They’re not. It’s a cheap thing that most people can don safely. No, it’s not comfortable to sit in a warm room to attend the Township meetings wearing masks. I’m happy to head back to the car and cool off. But the hard plastic chair isn’t a big cushy couch. Their building is drafty and, while I am certain the space is conditioned, the ambient temperature isn’t as comfy as my house. There are lots of ways in which the environment isn’t comfortable. Masks are generally available — back in March, I wondered why more people didn’t just wrap a scarf around their face a few times.

People argue the efficacy of masks — most of which seems to stem from early recommendations against mask wearing that was partially driven by the reality of product availability and partially driven by the unknown of aerosol v/s large particle transmission. And, for large particle transmission, just staying physically distant from others minimizes risk. But the reality is people don’t maintain an acceptable physical distance from others. Our Township meetings have board members sitting at the far side of 6′ tables … but they move their chairs around and end up four feet apart and yelling at each other. There are people walking right next to us in the grocery store, people queuing up a foot behind me at the liquor store, people standing next to us in the aisle at Home Depot.

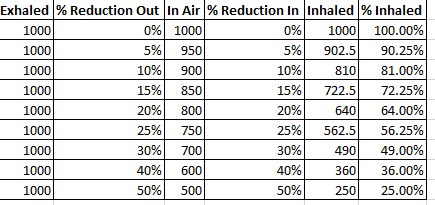

Even if a mask only prevents 50% of exhaled viruses from escaping and and prevents 50% of virus particles from being inhaled — that’s a huge reduction in risk. Even at 5% reduction, you’re reducing virus particles by a non-trivial amount.

I’m waiting for the lawsuits to start — it would be difficult to prove causality on a micro level (i.e. no one can sue Home Depot for failing to require customers wear masks), but at a macro level? Streets and businesses don’t altruistically have wheelchair accessible entrances. They have to. There’s a long legal history behind the requirement. Why shouldn’t businesses and government offices have to ensure access for those with compromised immune systems by requiring everyone wear a mask?